Artwork Obscura Fähigkeit

Portfolio Entry

On my way home, I encountered an animal jaw standing outside my door.

Artwork Details

-

Title:Obscura Fähigkeit

-

Year:2025

-

Medium (Type of Art):installation art

-

Unique Feature:includes a 20-minute sound art composition, played on loop

-

Medium (Materials):seaweed strands, polypropylene thread, linden wood strips, handcrafted hybrid fibre created with seaweed strands and polypropylene thread, bolts and nuts, cable clamps, turnbuckles, steel wire rope

-

Dimensions (International):100 square metre

-

Dimensions (British and US):1076 square feet

-

Venue:Kleine Kunsthalle (Theater), Theater Expedition Metropolis (ExMe) Berlin, Germany

-

Setting:Die Höhle_festival

Ethical Statement

During this work, no living creatures were harmed or disturbed.

Part of a Research Cluster

This artwork is part of the Coincidental Creatures research cluster, which explores the intersections between artistic practice and living beings. To learn more about the ongoing research and related works, please visit the Research Cluster page.

1. On the Title

The title of the work is a mix of Latin and German.

I derived the Latin word "obscura" from the phrase "camera obscura," which means "dark chamber"[1].

The term "camera obscura," as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, refers to a device, a space and an effect in which light passing through a small hole creates an image on a surface opposite the opening[2].

According to the Oxford Latin Dictionary, the adjective obscūrus has several meanings: "dark," "Hidden from sight," "(of sounds) Not clearly audible," "Imperfectly known (through lapse of time)," and "Not clear to the mind, incomprehensible, obscure"[3].

The German word "Fähigkeit" means ability or capability[4].

The word "Fähigkeit" is intended to evoke the resonance of the local environment, in which the work is being shown for the first time, while maintaining a broader, universal dialogue.

2. Central idea

I've been exploring new ways to collaborate with non-human organisms.

I share one possible perspective, knowing that others will see things differently. This variety of viewpoints is part of the work.

From my perspective, these collaborations unfold as mutual responses.

I show that the actions of non-human organisms matter. I aim to create awareness of their actions in a global context.

In this way, I try to listen to the actions of non-human organisms. At the same time, I am aware of the inherent limitations of understanding a non-human perspective. In turn, I receive creative inspiration.

3. How it Works

The process begins with a coincidence. This coincidence leads to an interaction between me and the non-human organism.

This influence guides my response in the creative process.

This method helps me acknowledge nature's work without appropriating it. I could work with the outcome of traces left by other living beings.

3.1 Example

For example, if a bird leaves a wooden stick on my windowsill, I might use it in my artwork.

I don't seek to impose my meaning on the object but to engage with it in a shared process. I see the gesture of the stick left on the windowsill not as something to take from but as an opportunity to connect. The stick stays what it is. My response contributes to the work. It does not claim ownership.

3.2 The Importance of Coincidence

I work this way because I believe coincidence can generate meaning.

Meanings are one of the raw materials in my artistic practice. My belief in the importance of coincidence is central to this work.

I recognise that coincidence may be different for others. Therefore, I see this line of research as a way to encounter even more perspectives on this topic.

4. What sparked the work?

One afternoon, I was chatting at a café about this line of artistic research.

On my way home, I encountered an animal jaw standing outside my door.

The jaw appeared separated from the animal, and I did not know why.

I guess that different cultures can interpret the presence of animal remains in different ways. To me, it felt like an inspiring coincidence.

This coincidence sparked my creative process. It was the beginning of this new artwork. The timing was important because I saw the jawbone right after that conversation.

The jawbone itself is not part of the artwork. The animal's remains appear as a sign that its physical life has ended. However, I think they can also evoke their presence in this world.

In this sense, my focus is on life.

5. Broader Inquiries

I see this line of research as connected to broader inquiries such as Posthumanism, Environmental Art, and interspecies collaborative practices.

The collaborative practice I am working on is spontaneous and unplanned. Randomness plays a role, but it emerges outside of human control.

I consider the actions of other living beings as equally significant as human actions.

The aim is to propose an artistic process that listens to the environment rather than imposing upon it.

At the same time, I remain attentive to the layers of complexity introduced by technologies.

6. How could it work this time?

Seeing the jawbone felt like a coincidence.

Previously, coincidences were associated with clear actions of non-human organisms. My response to the action sparked the creative process.

But how could it work this time? When all I had was a fragment of the non-human presence?

The point is that I was missing the context.

I didn't know why the jawbone was on the street or which animal it had belonged to. I could have tried to identify the animal, at least. Would identifying the animal give me context?

7. The Missing Context Becomes the Artwork Itself

An expert could identify the animal. I guess an expert could propose a likely context through several kinds of interpretation.

However, as an artist, I think I can expand the field of the assumption. I mean, I can use creativity to make new, hypothetical contexts.

I don't want to replace or deny existing interpretations. I think I can broaden the very idea of what "context" can be.

Can imagination help illuminate unseen connections or possibilities?

Could imagination be a source of bias or, on the contrary, an open door to alternative points of view?

The missing context becomes the artwork itself. The context shapes its interpretation.

8. The Key Elements Used in the Artwork

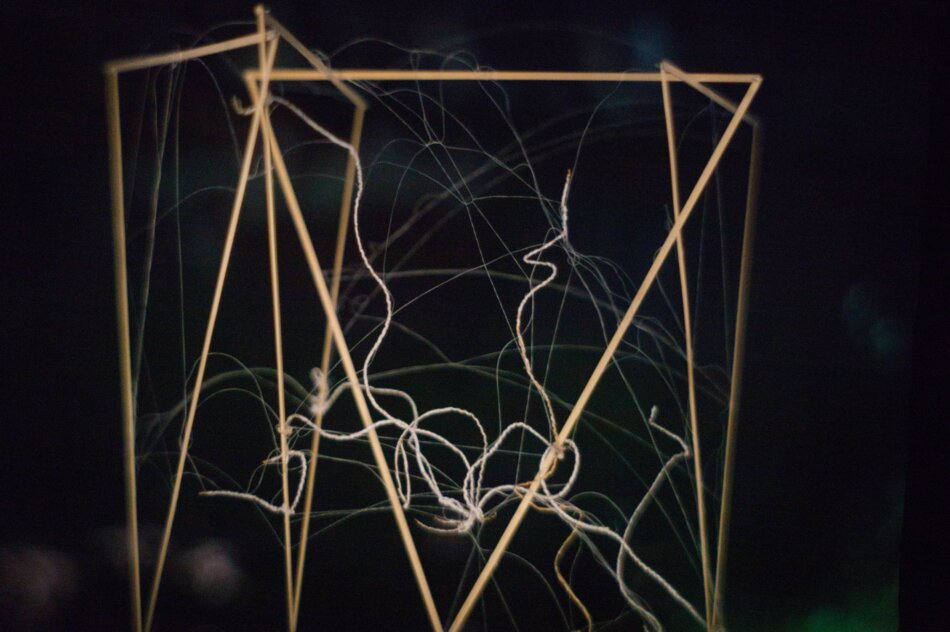

The key elements used in the artwork are seaweed strands, polypropylene thread, and linden strips. I chose each material for its connection to the theme.

I chose the seaweed because I imagined that the animal that belongs to the jaw comes from the sea.

The jaw is on the street in an urban context, not close to the sea.

What if the area was underwater centuries ago, or perhaps it will be in the future?

What is the evolutionary history of the animal that once belonged to the jaw? Do their ancestors come, for example, from water?

The creation of a context could lead to concrete questions. The relationship between imagination and knowledge appears complex.

The seaweed strands come from seaweed twine. I separated the two strings from the twine to obtain some strands.

The idea is that this gesture reverses the industrial process, I mean, the process that twisted the natural fibre into twine.

To highlight the layered relationship between the natural and the industrial, I intertwined the separated seaweed strands with polypropylene thread.

Finally, with the linden strips, I built four triangles. They are the faces of a tetrahedron, the geometric structure that could remind one of the spongy bone of the jaw and the lighting trusses where I hung the artwork.

I assembled the triangles in the artwork in an unstable way. I called this structure an unstable tetrahedron. This idea follows my main thread of my body of work, the instability of rule systems.

Introducing the linden tree, I created a form of displacement. The linden contrasts the imagined marine context, bringing in a reference to the physical, urban context. I imagined the context as a sea. The linden tree was physically present near where I saw the jaw.

9. A Dark Room

I overlapped the imaginary and the concrete, aiming to create a space for different interpretations.

The idea of displacement is crucial.

The viewer experiences the work indirectly. It appears as a picture projected in a dark room, a "camera obscura."

The festival curator created this format, and all artists follow it.

I wrote some reflections on the camera obscura in "The Ontological Shift in Fixing an Image from Camera Obscura to Photography."

10. Deepen the Interplay of Senses

Then, I created a musical composition. I applied the same pattern that I used with the fibre to develop it, combining organic and artificial elements.

I recorded the sound of fracturing linden wood, capturing a raw sound.

On this webpage, you can play the sound of cracking wood. I offer it as a document of the process, something extra, not essential to the experience. Some listeners may find this sound uncomfortable. If that's the case, you're welcome to skip it.

At the beginning, this sound inspired the final music composition. Then, I develop the composition in a different direction.

I added a synthetic tone over it. In this way, I felt I merged the organic with the artificial, like with the fibre. Listen to the composition, and one can have the sensation of something fragmented. The fragment is a referent to the jawbone, something isolated from its environment and disconnected from its original body.

The sound plays inside the dark room. It is, indeed, part of the artwork, and the idea is that it opens another sensory dimension.

In a nutshell, the audience's experience of the work is indirect, mediated through light.

The light enters the dark room from outside. Then, it projects an object placed on a theatrical stage, but the stage remains inaccessible to the audience.

The audience also experiences the artwork as sound within the dark room.

11. What this piece proposes

I found the jawbone, and this encounter created a point of intersection. It was an imaginative point between organisms.

This point sparked a creative response. That means that a broken fragment can open new pathways.

I felt like a transferring creative intelligence. In the same way, the object in the installation moves from outside to inside the camera obscura, transferred, one can say, by light.

12. Final Notes

At the entrance, the audience can read the artwork statement or view it in the digital version on their own devices.

During this work, no living creatures were harmed or disturbed.

Notes

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "camera obscura." Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2025., accessed April 20, 2025,https://www.britannica.com/technology/camera-obscura-photography. back to the text

- Cambridge Dictionary, "camera obscura," accessed April 20, 2025,https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/camera-obscura. back to the text

- Oxford Latin Dictionary, s.v. "obscūrus" (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 1220. back to the text

- See, for example, Collins German Dictionary, s.v. "Fähigkeit," accessed April 20, 2025, https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/german-english/fahigkeit. back to the text

Author: Vincenzo Fiore Marrese

Published on: April 11, 2025

This article was originally timestamped on: April 11, 2025

This article was updated and re-timestamped on May 5, 2025.